ISO Quality Management System Series: Part 2

Lately, Evaero’s internal results have plateaued and measurable improvements have been hard to come by despite our effective quality management system (ISO 9001:2008 and AS 9100C).

As noted last week, the quality management system (QMS) has contributed to a reduction in errors in precision CNC machining aerospace parts thereby reducing operating costs and the likelihood we’ll ship bad hardware.

In our last ISO/AS audit during casual conversation we noted that spending money on a quality management system had similarities to spending money on the war on poverty:

- The effect of not spending the money is much greater than you can predict.

- Regardless of the amount of money spent, you’ll always have some poverty.

- You’ll struggle convincing many people it’s money well spent.

Thinking about this further, it’s clear that how one views the underlying foundations of poverty has a big impact on the systems that are setup to eradicate it. In other words, someone viewing poverty through the lens of human rights will come up with fundamentally different programs than someone who believes the roots of poverty to be grounded in say, education.

Likewise, it wasn’t until I viewed our QMS through a different light that I realized we needed to consider the possibility some of our internal errors were grounded in something fundamentally different; something not currently considered by our existing system.

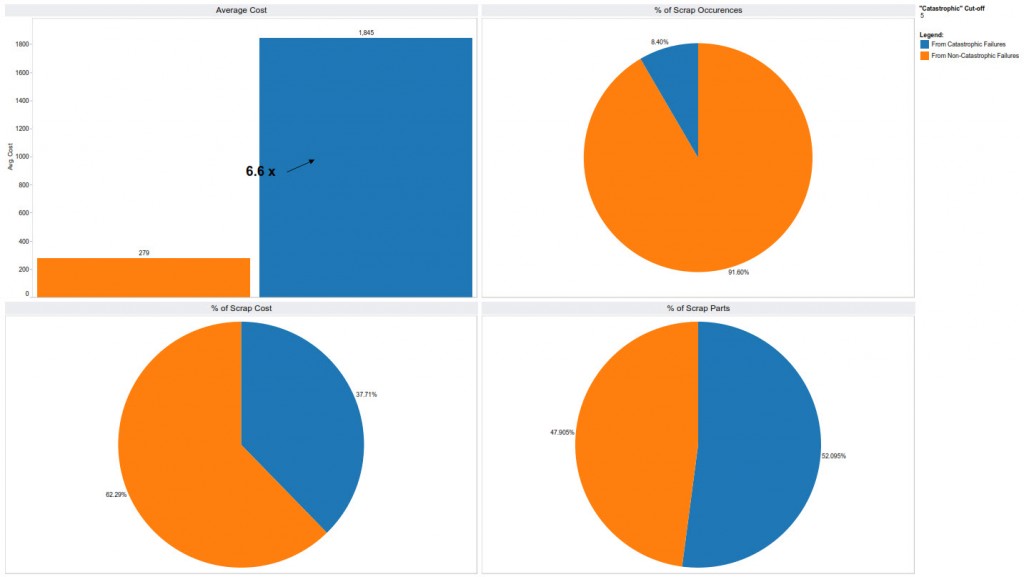

After reviewing aggregate data* it has become apparent to me our errors can be grouped as either “failures of the predictable kind” or “failures of the unpredictable catastrophic kind,” where I arbitrarily define a catastrophic event to be one that results in five or more non-conforming parts (NCs). Considered as such, data collected over a few years show that 8.4 percent of occurrences result from failures of the unpredictable catastrophic kind.

What’s interesting about this is that while these failures occurred less than 10 percent of the time, they in fact represent 40 percent of the total money we lost due to errors and over 50 percent of the total number of parts lost.

Furthermore, the average cost of a catastrophic failure was 6.6 times greater than an everyday sort of predictable failure. All of these data are outlined in a single graphic that can be viewed here:

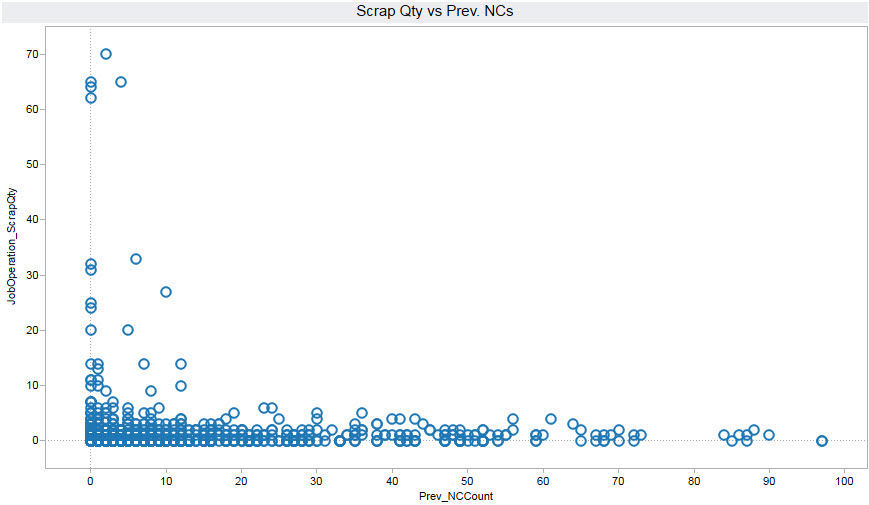

In an effort to further characterize catastrophic failures I wanted to get a sense for the history of a particular operation before the failure occurred. Consider the plot titled Scrap Qty. vs. Prev. NCs where each data point represents an instance when an operation was run during the last couple years.

The data points are positioned on the graph according to how many parts were scrapped during that particular operation (y axis) and a summation of the total number of non-conformances for that operation prior to that moment in time (x axis).

Note that instances with large abscissae typically represent operations that have been run many times. What is observed is that catastrophic failures occurred during operations that had not previously produced parts with many non-conformances. The operations with a history of intermittent problems on the other hand are not resulting in a critical event that leads to a large amount of scrap during a single operation.

What these data show are that while we are managing the predictable issues, we’re not minimizing the impact of random unpredictable failures. One might perceive that other than building in redundancy, there isn’t anything you can do about the random and unpredictable.

As a lead-in to next week’s post, consider what Netflix does to keep it’s network running most of the time. As systems become ever more complex and intertwined, this becomes more and more important.

In a blog published by Netflix technicians, Chaos Monkey Released into the Wild, authors Cory Bennet and Ariel Tseitlin note the following:

We have found that the best defense against major unexpected failures is to fail often. By frequently causing failures, we force our services to be built in a way that is more resilient.

The Chaos Monkey is software that Netflix allows to run during a limited set of hours with the intention of causing network failures. However, because their engineers know it’s running, everyone is on alert and able to respond. In other words, they intentionally stress their system to make it better.

Don’t think this applies to your business? Consider the following quote from the same article and swap out the word “software” with what you do for a living:

Software is complex and dynamic and that “simple fix” you put in place last week could have undesired consequences.

As a result of commoditization, even businesses that we don’t normally think of as complex and dynamic are so; yet, we continue to apply the same reactive formulas to making improvements.

Take the cantaloupe I happen to be eating while I’m rushing to meet my 8:45 AM deadline for this article. In addition to cantaloupe’s unique skin which can trap and hold bacteria and “animal vectors in the growing environment” (i.e., animals shitting on produce) think about the complex supply chain involved in getting that melon to your table: growers, harvesters, packers, storage, transportation, distribution, processing, the retailer, and you. Consider also what was uncovered after 33 people were killed and hundreds sickened when listeria-infected cantaloupe made it to the consumer:

Investigators and health experts eventually descended on Jensen Farms and would determine that the outbreak occurred because a pair of brothers who had inherited the fourth-generation farm had changed their packing procedures, substituted in some new equipment and removed an antimicrobial wash.

Of course, in hindsight the experts with no skin in the game tell us this could have been prevented (don’t they always?). What I see is a complex and dynamic system that had a “simple fix” put in place by two brothers that in turn led to undesired and unpredictable consequences. Sound familiar? Has something like this ever happened in your business?

Needless to say, it’s great we’re able to binge watch a season of House of Cards without a single network issue (thank you, Chaos Monkey!) but I hope you’ll agree the stakes of failure are much higher in other industries.

As such, as systems become ever more complex and intertwined it’s crucial we ask how we can fail in a manner that our systems of production can become more resilient and limit the effect of future failures of the unpredictable catastrophic kind.

If you’ve made it this far, thanks – I promise to tie all of this together next week. Until then, in the words of Brittany Howard of the Athens Alabama based quartet Alabama Shakes (hat tip Amanda), “you got to hold on.”

Cheers–xian

Video not displaying properly? Click here.

*Special thanks to James Spezeski for helping with data analysis and reporting.