By nature, I’m extremely risk averse. Simply put, I avoid putting money on the table unless the odds heavily favor a positive outcome, or the downside to risk can be limited. Over the years, one of the things I’ve come to terms with is how to stay true to myself in this regard despite being in a business where the risks are high and the profits are low.

Let’s talk about some of the risks.

For starters, the capital outlays required for plant, property, and equipment (PPE) in our industry are significant. CNC machining centers are expensive but so too are the things needed to bring the equipment online: power, air, metalworking fluids, tool holders, accessories, etc. How much you’ll spend depends on too many factors to list but suffice it to say, you’re talking about hundreds of thousands of dollars per piece of equipment. Add to that the tangible personal property (TPP) taxes some states like Arizona charge and not only do we contend with the up front costs but also annual costs associated with taxation.

A hidden and often overlooked business risk to aerospace cnc machining companies like ours are the dollars tied up in inventory. Manufacturers are obligated to cover the costs (e.g., labor, material, processing) associated with the parts in inventory up front. When customers suddenly stop buying, the risk of suffering a liquidity crises is high.

Furthermore, because the products companies like Evaero make are unique to a particular customer, each part put into inventory is similar to making a “naked put” trade. You technically “own” the part in inventory; however, because it has no value on the open market, should your customer decide not to exercise the contract the downside is zero dollars. Indeed, when you consider that many manufacturers are forced to maintain inventory positions equivalent to a third of forecasted revenues, the risk can be quite large.

Finally, more often than not, there is a “j-curve” associated with bringing new products online. Today, if you want to get on board with new platforms, the expectation is that vendors share the risk by shouldering their part of the startup burden. As such, as programs come online, we need to be prepared to absorb losses for a period of time before making money. If, however we don’t own the intellectual property associated with the good we’re making there is nothing that prevents our customer from going elsewhere just as we’re trying to pull out of the j-curve.

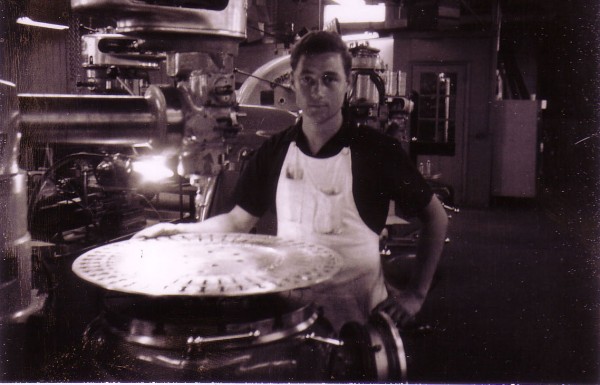

Many years ago, when we lived in Union, New Jersey, my father worked for a small privately held precision CNC aerospace machining company based in Scotch Plains. At the request of their (only) customer based in Michigan the company moved to Tucson, Arizona to be closer to what, at the time, was called Hughes Missile Systems. Doing everything right along the way for their Michigan based customer in terms of price, quality, and delivery their small company quickly changed and grew to over 200 people.

Unfortunately their customer also went through some rather large changes: the company was bought out, new management brought in, and a new manufacturing plant was opened in another state to get relief from the local union.

As a result of one/some/all of those reasons my father’s company was given a year notice. At least they got a year.

We didn’t see much of my father that year but the business (and his marriage) would in fact live to see another day. Barely. Hard work, persistence, and luck all helped to save the business and so to did the fact that the business shouldered none of the risks outlined above: the equipment and building were mostly owned outright; they had no inventory; and their customer had been paying them for all developmental work.

Clearly business conditions in our industry today are different than they were during my father’s generation, as are the risks. There are however, lessons to be learned from my father’s story and I look forward to drawing on them when I tie all of this together after next week’s blog on the reward side of the equation.

Thinking about my dad and the amount of time he spent away from his family working and my own current role as a father reminds me of the French song Papaoutai by the Belgian singer-songwriter Stromae (hat tip Gregory).

A little about the title of the song. The standard way to say “Father where are you?” in French is “Papa, où est-ce que tu es?” In familiar French this becomes “Papa, tu es où?” or “Papa, t’es où?” when speaking fast. Alternatively you can say “Papa, où t’es?” which is in fact where the title of the song comes from.

The song has some great lines. A couple of my favorite are:

Tout le monde sait comment on fait les bébés

Mais personne sait comment on fait des papas

Which translates to: The whole world knows how to make babies but no one knows how to make fathers.

I was shocked to see that the video has been watched over 237 million times and it’s definitely worth a view (see below).

Until next week.

In your service…xian

Video not displaying properly? Click here.